Indian Philosophy 101

Years ago, when I was an undergraduate student, I took an elective course in Indian philosophy. As a Linguistics major, I had been studying Japanese language and history, and I was drawn to the Buddhist philosophy that is so deeply woven into Japanese culture. As Buddhist traditions have their origins in India, I thought a course in Indian philosophy might provide useful context for the evolution of Buddhist sects in Japan.

The textbook was a course pack of carefully selected photocopies from various classical sources. Each page was different: passages in Sanskrit were sprinkled throughout, and some copies required the tilt of the head to read, their words flowing off the page and into the ether. The professor had closely cropped hair and wore a wide-sleeved floor-length caftan. She wasn’t from India but had spent a lot of time there and was very well-respected. I wish I could remember her name.

The class was small and quiet. Most of the lecture time was dedicated to the painstaking analysis of the texts. To be honest, not much of the material stayed with me. I remember words like Atman and Brahman, and there seemed to be questions around whether they were the same things or different. There was Arjuna and Sri Krishna and some kind of discussion about a chariot. The professor seemed very interested in the meaning of this particular chariot.

Though I don’t remember much of the material, I remember the experience. There was an energy of uncertainty around the professor, not about the topics, but about the classroom. It was my impression that she was not used to teaching in such a context. The formality of it did not seem to suit her. Her caftan would billow around her as she talked, almost as if it was preparing for her to sit down. And if there had been a meditation cushion nearby, I feel like she would have been quite happy to sink into it. From time to time, she would look up from her notes and search the room for expressions of understanding, it seemed, or, at the very least, acknowledgement. She seemed concerned that there wasn’t more engagement from students.

After class, she would sometimes ask me questions about how the work was going, and whether the pace was alright. Did she need to explain that topic again? Were there any questions?

Every week, I would answer that all was well and that we were just a quiet group. But one day, after a few questions, I turned to her and explained very honestly that the material was confusing and that I was not sure, at any given moment, what was the correct interpretation and what wasn’t.

She nodded, gave me a mysterious smile, and said thank you.

I understand that smile now more than I did then.

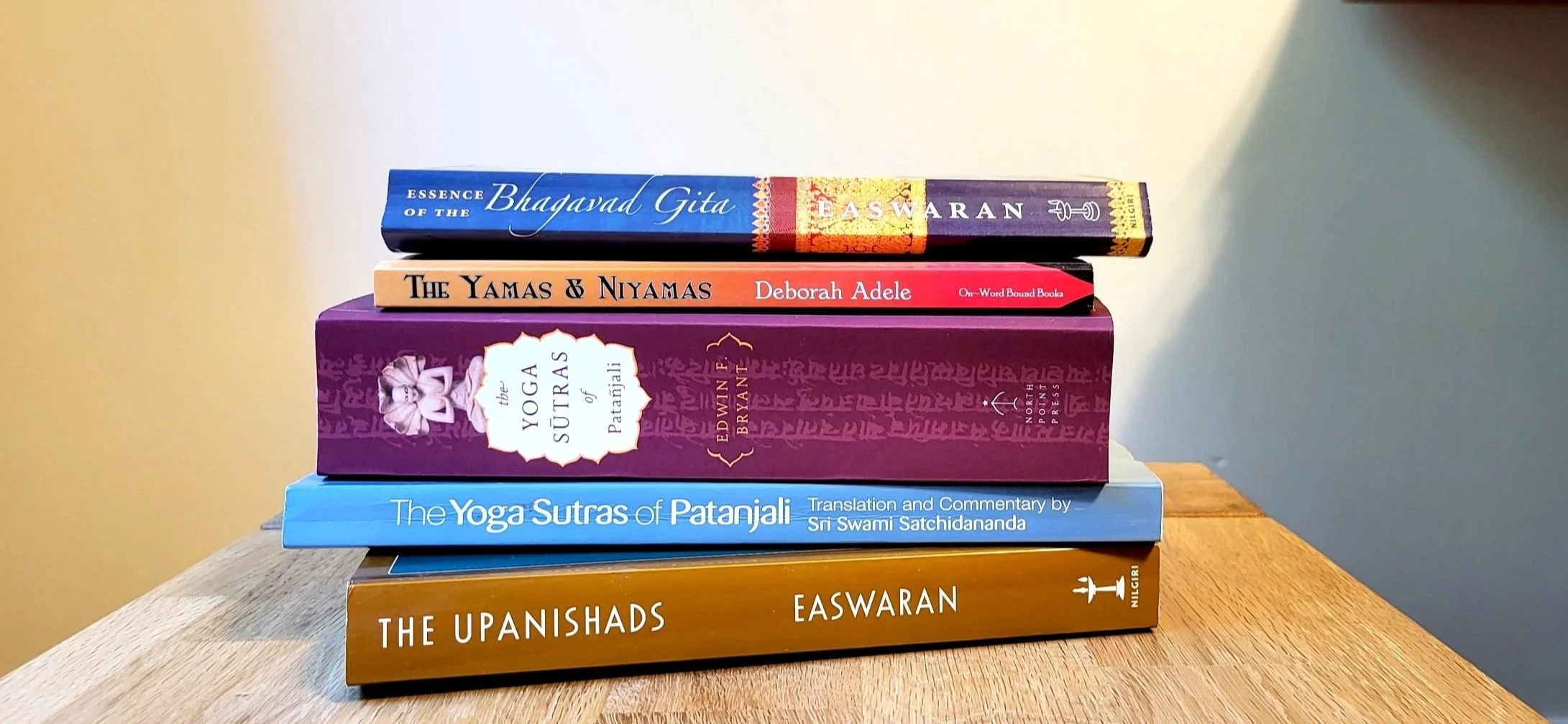

It’s a shame that my course pack got lost in the shuffle of years. I imagine that its highlighted sections, markings and incomprehensible notes in the margins would have felt a little bit like home. I’m sure that if I looked at it now, I would recognize some of the texts and passages.

The funny thing is that around that time, I was practicing asana in my basement with DVDs by Rodney Yee and Shiva Rea. But to me, the philosophy I was learning in the classroom and the asana practice I was experimenting with bore no connection to each other. It never occurred to me that the philosophical concepts I was learning in the classroom had any practical application, and it never occurred to me that asana was an entry point for such an endeavour. Rodney Yee was just a guy who made yoga DVDs on beaches and hillsides. That was it.

I was young at the time and hadn’t yet had the life experience to put these pieces together. Little did I know that I would make a return to the concepts of Atman and Brahman, or that I would read and re-read the Bhagavad-Gītā. Perhaps my current understanding, as it evolves, is only part of the process, and, as some would say, the yoga journey. But the natural disconnection of philosophy from asana in my younger years, a result of inexperience and age, is an individual rendering of a much larger pattern. In the West we tend to take holistic systems from other cultures and compartmentalize them in such a way that they lose much of their meaning. Failing to see that threads woven together are much stronger, more resilient and more unified is one of our greatest weaknesses.

I could not have known back then how often over the course of my life yoga would come back and invite me in or how the pieces of my life would come together. But inevitably what is meant to be woven will be. Threads come together. Pieces fall into place.

Thank you for being here.